Six days after our introduction to Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon we were on our way to Taiwan for the filming of The Sand Pebbles. It was less than two years since I had read Richard McKenna’s book and had brought it to Steve's attention. He had immediately identified with the character of seaman Jake Holman and was delighted when he was approached for the film version. We had been especially thrilled to learn that Robert Wise was directing and producing. The last time Steve had worked for Bob Wise, he had been a bit player. We had also eloped to Mexico while I had been in the middle of a Bob Wise production and Steve had been steadily unemployed. Now here he was, starring for this widely acclaimed director in a multimillion-dollar epic. What was also nice was that Solar was coproducing the film for Twentieth Century-Fox with Bob's production company, Argyle Productions. Co-starring with Steve were Richard Crenna, still a close friend, and Richard Attenborough, with whom Steve had worked on The Great Escape. Steve's love interest was the ever beautiful nineteen-year-old Candice Bergen.

My first impression of Candy was that of a Jewish American Princess stranded in a strange land with strange people.

I remarked to Steve how very pretty she was and that I found her to be very shy and so young underneath all her seeming bravado.

"And horny," Steve said. I wasn't sure I heard him right.

"Say that again?"

"She's horny, I said," my darling repeated.

I looked at him and shook my head in exasperation. "For you, I suppose?"

"No, in general, is what I'm sayin',” said my all-knowing master.

Poor Candy Bergen, I thought. Those guys who are here without their wives are going to be hitting on her. But Candy was smart. Much smarter and much more of an intellectual than I had initially given her credit for. From what I observed she wasn't particularly keen on socializing with the cast of ruffians. Instead she became friendly with the very gentle Sheila and Dickie Attenborough, who were more on her wavelength.

The film was to be shot in Taipei and Hong Kong and their outlying areas and was expected to take nine weeks. Because of our past experiences with foreign locations my instincts told me this movie would not come in on schedule, and I prepared us for the long haul, packing a trunk for each of us, leaving Mike-the-Dog with friends and closing the house down. And I was wise. The night before our departure Paul and Joanne Newman came to wish us well. The last words Paul said to us as they drove down the driveway were "See you in nine weeks!"

The film was to be shot in Taipei and Hong Kong and their outlying areas and was expected to take nine weeks. Because of our past experiences with foreign locations my instincts told me this movie would not come in on schedule, and I prepared us for the long haul, packing a trunk for each of us, leaving Mike-the-Dog with friends and closing the house down. And I was wise. The night before our departure Paul and Joanne Newman came to wish us well. The last words Paul said to us as they drove down the driveway were "See you in nine weeks!"

We came home seven months later.

Twenty years ago, Taiwan was the pits. There is no other way to describe it. It was dirty and malodorous, and because the country was technically at war with Red China, it was also, for all intents and purposes, a virtual military base. Army trucks continually rumbled through the crowded streets of Taipei and uniformed personnel were visible everywhere. The war in Vietnam had been escalating rapidly and Taiwan was being used by our troops for "R and R." Ten days prior to our production start a defecting Communist pilot crashlanded a Russian bomber outside of Taipei, and a week before filming began, Nationalist Chinese gunboats fought a furious battle in the Formosa Strait. We were all issued special identification cards and all of us underwent security checks. Bob Wise's production manager assigned an interpreter to each of the thirty-two key crew members.

For the filming of the best-selling novel a gunboat from another generation had been reconstructed down to the very last rusty bolt and had sailed the China Sea and the Strait of Formosa. Because the Taiwanese government had just begun a vigorous campaign promoting tourism and was mindful of the economic gain to be wrought from a major movie production company, The Sand Pebbles had a far easier time of it than another Twentieth Century-Fox film had had a few years back. The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, starring Ingrid Bergman, had run into script difficulties with the government. Rather than allow Taiwan to dictate to them what their script should say, Twentieth Century-Fox just packed up and left. They instead went to Wales, where they constructed their very own Chinese city. This time the Taiwanese tried not to interfere (although, unaccountably, we all noticed that our daily editions of the New York Times would arrive with stories missing and pages ripped out). Even though I tried to deny it, the place made me very uneasy. I was careful not to convey my feelings to Chad and Terry, who were then five and six-and-a-half. As was our custom, we had brought them with us, and they were attending school. I wanted them to enjoy themselves and the experience of living in a new land. Steve insisted that we live in our own house rather than stay with the rest of the crew at the comfortable Grand Hotel, which was owned by Madame Chiang. Our house was surrounded by farmland and came with a Chinese cook and amah (nanny). Our situation wasn't all as pastoral as it sounds. Since Taiwan's popular form of fertilizer consisted mainly of human excrement, when the winds blew toward us all the windows had to be shut. Steve used to. say, "The reason there's so much rice on this island is because the rice can't wait to get out from under to get some fresh air!" One day Steve took the children bike riding about the surrounding countryside and for some reason all three slipped and fell into a recently fertilized rice paddy. When they returned home I refused to let them in until I had stripped them and hosed them down! Toward the end of our stay in Taiwan the popular saying among cast and crew was "You know you've been here too long if you can't smell it anymore!"

Filming began in Taipei on November 22, 1965, a wet, dreary morning. The children had already left for the Dominican School and Steve was inside the house frantically trying to reach the production office. His jeep wouldn't start and we had a twenty-mile drive to Eight-Foot Gate at Keelung, where the USS San Pablo was berthed and where the day's shooting was to be. They located Clap-Clap Shapiro, a local who had been hired to perform odd jobs for the company, and dispatched him and a driver to our house. As we rushed out Steve said, "Never been late to a set in my life," and quickly commanded Clap-Clap's driver to move aside so he could drive. As the driver and Clap-Clap groaned, Steve assured them with, "Don't you worry, now. We'll either get there alive or we won't get there at all." I turned my head and saw the panic in their eyes. In the few days we'd been here these men had already heard of Steve's mania for speed. I suppressed my laughter. As he began racing the Buick on the MacArthur Freeway Steve yelled, "How are the brakes?"

"Fine. I hope you don't get us in a ditch, Steve," came the nervous reply.

"Hell, if we go, we go end over end!"

Steve slowed down for buses and big trucks. The rest were honked aside. When the Buick finally skidded into the Keelung toll station, Steve was relieved and said joyfully, "Hey, we got it made!" As Steve hit the brakes at The Sand Pebbles set he turned, grinned widely, and offered his hand to Clap-Clap. "Thanks, man."

Clap-Clap Shapiro and his driver were in a state of collapse and could barely mutter a sound! Steve had made the twenty-mile drive in thirteen minutes, and there was no production time lost.

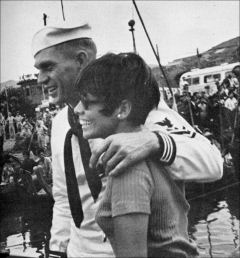

The GIs stationed on Taiwan had welcomed the movie company with open arms and had given us PX and the Officers' Club privileges. I organized and taught exercise classes at the club for the military wives, and just before Christmas I went to Quemoy for the day to entertain the three thousand men on that island. At that time, the danger was very real and the military air transport bearing me and the other performers had to fly at low level in order to avoid radar detection.

As Christmas approached, the children, Steve, and I went shopping for a tree. We bought what we thought was the best Christmas tree and when we arrived home we discovered as we untied it that branches had been wired onto the trunk to make it look thick. It looked thick all right, except that the extra branches all drooped. After we recovered from the shock we laughed and decided to keep the droopy tree anyway and to celebrate Christmas in the best Taiwanese spirit. Perhaps as a reward for our good cheer, we learned that the Hollywood Women's Press Club had given Steve its "Golden Apple" for being the most cooperative actor of 1965 (this we looked at as a Christmas present)!

In Tam Sui, where the USS San Pablo was currently docked, a twelve-foot Christmas tree was hoisted to the foremast of the gunboat and was spotlighted at night as a tourist attraction. I believe the tree came from the black market, where one could purchase anything and everything for the right price. The day after New Year's the tree came down and filming resumed. Or at least the attempt was made. The weather had turned so unpredictable that four call sheets (which are actors' and crews' assignments) were issued daily. And even then, shooting around the weather caused long and frustrating delays. Boredom and restlessness inevitably set in. While the men couldn't go anywhere since they were usually on call or working, the wives could at least get off the island for a while when claustrophobia set in and go to Hong Kong or Singapore or other neighboring islands for a day or so.

I made two such trips, one to Hong Kong to enroll the children in the Maryknoll School, which they would attend during that phase of the location (it was the same school I had been to as a child); and to Manila, which I was eager to see through my now grown-up eyes. It was an emotional journey for me - how far I had come in these seventeen years!

While we were on this location Steve became enamored of cinnamon toast for breakfast. He never liked to deviate from whatever was his fancy of the moment, so every morning I gave him his two pieces of cinnamon toast and coffee with three sugars and a lot of milk. One day he said, "I want two pieces of cinnamon toast to eat here and two for the road." I thought that was a reasonable request. The next day he wanted two at home and four for the road. I thought, well, why not? The man works a hard day. The day after that it was six for the road, then eight, then ten, then twelve. I became suspicious. I said, "You can't possibly be eating all that!"

"Why not? I like it," he said. So I went to the set, made a few inquiries, and found out he was selling the toast to the crew for ten cents apiece!

The cinnamon toast also became useful for bartering. Dick Crenna later told me that when he first came on location, he had found it difficult to establish a rapport with Steve. It wasn't that Steve was cold, but that he preferred to hang around the set with his kind of guys, mostly stunt men. Then one day Steve said to Dick, "Let's talk about our parts," and Dick thought, Oh, God, here's the superstar to tell me how to do it. They spent five hours in a hotel room discussing their roles, and it was a breakthrough. In that moment, Dick came to respect him. But Dick also explained that because of his role as the ship's captain in the film, he had been given the captain's cabin on the San Pablo for the duration of the shooting, thereby segregating himself from the rest of the company, including Steve. With a crew as large as The Sand Pebbles, cramped day after day on a 150-foot gunboat, that cabin was a real luxury. Dickie Borough had moved in with Dick, and then after weeks on the San Pablo, Steve walked in one day and said, "If you let me in I'll give you my coffee and cinnamon toast." That did it: Steve was in!

As is wont to happen during a long location, there were two accidents. While I had been away Chad had burned his tiny hand. Steve said he hadn't cried or moaned and that had pleased Steve enormously. Chad had just looked up at his father, who had said, "Well, Chad, another burn, another scar. That's what the world is all about, son." Then Steve had given him a big hug. Steve believed with all his heart that the true measure of a man is how much he can take and not show it. The problem was that inside, though, he churned like an angry sea in a typhoon.

As is wont to happen during a long location, there were two accidents. While I had been away Chad had burned his tiny hand. Steve said he hadn't cried or moaned and that had pleased Steve enormously. Chad had just looked up at his father, who had said, "Well, Chad, another burn, another scar. That's what the world is all about, son." Then Steve had given him a big hug. Steve believed with all his heart that the true measure of a man is how much he can take and not show it. The problem was that inside, though, he churned like an angry sea in a typhoon.

In the second accident, several members of the crew were dumped into the Keelung River when a fifteen-foot camera boat sank. The boat was lashed in tandem to two other boats bearing Steve and Dickie Attenborough, but the actors escaped a dunking. The very expensive Panavision camera was saved, but other equipment, including a sound control panel, went to the bottom. The camera assistants had taken a dunking, but all had swum safely ashore. Nonetheless, the incident set the film's schedule even further back.

One morning Jim Garner called from L.A. with some aggravating news. As soon as I was assured that nothing had happened to our house (he was, after all, our next-door neighbor) or to Mike-the-Dog, whom we had had to leave home, I handed the phone to Steve. I sensed something was very wrong and when he bid Jim good-bye Steve stared straight ahead, not saying anything. I waited patiently for him to collect his thoughts. Then slowly and deliberately he said, "That fucker. He's just signed to do Grand Prix. He wanted to tell me himself before I read about it or heard it from somebody else. How about that? You see, baby, you just cannot trust anybody in this business."

"Honey, come on now, be reasonable," I pleaded. "I hate to tell you this, but you're overreacting. Look. You were asked to do the picture, but you didn't want to. Jim is an actor. You cannot begrudge him for accepting a part that somebody's going to do. I mean, it could have been Paul Newman or Jim Coburn just as easily. Obviously the producers have to go for a big name. They're not dummies. They're not going to hand the picture to some unknown just because these stars are your friends! Honey, you do see what I mean, don't you?"

He did see, but he didn't like it. It was two years before Steve would speak to Jim, although even then he really never felt the same way about the man again. Steve pouted and felt he had been betrayed and that was that. I felt bad because we had shared so many good times with the Garners. For instance, just before we left for Taiwan, Paul Newman, Jim, and Steve and I went to the races at Riverside. On our way home, the man became annoyed because I had insisted on stopping at the next service station rest room. They had hoped to beat the traffic home. When they did stop I discovered to my dismay that there was a long line of women ahead of me. Unable to stand the delay any longer, I came up with a brilliant idea. I said to the girls standing there, "Hey, do you know there's a car full of movie stars around the bend?"

"Who?" they cried in unison, "Why, there's Steve McQueen, there's Paul Newman, and there's James Garner!" The girls looked at each other and ran like crazy, leaving me in sole possession of the facilities. I never did tell the fellas how a swarm of females suddenly discovered them!

Now, to make our scheduling problems worse, John Sturges arrived on March 2 in Taiwan to discuss Day of the Champion with Steve. The Sand Pebbles was way over schedule. No one knew when the company would be moving on to the next location (Hong Kong), nor could anyone assess how long we would be there. In the light of these realities, the planned May start date for Day of the Champion had to be pushed back. Even July was looking "iffy." So John zeroed in on August.

But there had been an unscheduled run-in over the validity of the Sturges-McQueen contract with the Nurburgring auto racing course. The producers of the competing Grand Prix, Ed Lewis-John Frankenheimer, had attempted to get an injunction against the Auto Club of Germany, with whom Sturges had a contract. However, the courts ruled the Sturges pact valid and twenty-seven reels of backgound film were released to John. To capture the track's atmosphere, Stirling Moss, now completely recovered from his near-fatal accident in 1962, drove a racing car with a camera mounted on top of it, traveling at speeds up to 175 miles per hour. The Nurburgring Grand Prix drew nearly 500,000 fans and was also covered by a helicopter.

Steve could hardly wait. Whenever he talked about Day of the Champion his eyes sparkled. He had found a kind of dignity in racing and the acceptance that had been given him by one of the toughest fraternities in the world was immensely satisfying. He was certain this epic would be the definitive film on motor racing. His hands were already itching for the wheels.

A few days after John's arrival in Taipei a large earthquake shook the area just before dawn. The damage to the island had been extensive and John, who was a philosophical man, decided he had had enough of the Orient and departed for the good old USA! He had concluded his business with Steve and there was no reason to delay his departure. How we envied him! For years after this Taiwan adventure Steve and I believed that anything we had ever done wrong on this earth was paid for on that location! Oddly enough, the experience seemed to make our relationship closer and stronger, possibly because there weren't many female temptations and possibly because Steve was relatively drug-free.

March 24 was Steve's thirty-sixth birthday. After four months in Chiang country we were finally in Hong Kong. Home was only a few weeks away and we could now look forward to an easier time. We could see the light at the end of the tunnel. There had been a tense moment in Taiwan when the whole company had been allowed to leave - that is, with the exception of Bob and Pat Wise, Steve, the children and me, and one or two other key people. The government had held our passports claiming that the production company owed Taiwan more tax money. It was a lie, but we paid them anyway. There was no choice. It was a case of pay or stay. To celebrate our release from Taiwan we observed Steve's birthday twice in conformance with Chinese custom. According to the Chinese calendar each month has twenty-nine or thirty days, depending on the moon, and every fourth year has thirteen months; 1966 was a fourth-year cycle and March was the repeated month. Hence, two parties!

The few weeks we expected to spend in Hong Kong turned into three months, and at last we were headed for home. It had been a tough location, and the film still had a few weeks to go on the sound stages at Fox. Steve looked exhausted and was suffering from an abscessed molar. He had refused to see a doctor until we got home. When we got off the plane in Los Angeles, Steve literally threw himself on the ground and kissed the American soil he loved so much.

When Steve finally allowed the doctors to check him, they prescribed enforced rest. He had been close to a physical collapse. Not only had the over-scheduled Sand Pebbles taken its toll on his health, but location shooting for the previously completed Nevada Smith had been tough. And before that had been The Cincinnati Kid, it was time for a rest. The man was clearly out of gas. Production shut down temporarily on Sand Pebbles, and it became disappointingly clear that the racing movie had to be temporarily shelved as well.

WE LAUNCHED our departure for New York and personal appearance tours for The Sand Pebbles with a sensational party in the courtyard of our house that lasted until the small hours of the morning. As soon as the tent went up, the set decorators from Twentieth Century-Fox immediately went to work to transform the Castle into the Red Candle Inn of Happiness, right out of the movie. There were colorful Chinese swinging lanterns, and scrolls, banners, and panels everywhere, lavish vases of flowers and greenery throughout the house, and a long buffet table of Chinese delicacies. The entertainment was provided by Johnny Rivers, now a big star, and a new rock group known as the Buffalo Springfield.

WE LAUNCHED our departure for New York and personal appearance tours for The Sand Pebbles with a sensational party in the courtyard of our house that lasted until the small hours of the morning. As soon as the tent went up, the set decorators from Twentieth Century-Fox immediately went to work to transform the Castle into the Red Candle Inn of Happiness, right out of the movie. There were colorful Chinese swinging lanterns, and scrolls, banners, and panels everywhere, lavish vases of flowers and greenery throughout the house, and a long buffet table of Chinese delicacies. The entertainment was provided by Johnny Rivers, now a big star, and a new rock group known as the Buffalo Springfield.

The invitations read "very informal," which in Hollywood can mean anything like tiaras for women and sneakers for men.

Joan Collins, as usual, was a party stopper in a red fishnet see-through dress (husband Anthony Newley was out-of-town); Jane Fonda, wearing a black vinyl miniskirt and jacket, was stopped at the bottom of the hill by a security guard because husband Roger Vadim's name had inadvertently been omitted from the guest list; Zsa Zsa Gabor was dressed in something that can only be described as a short, black sequinned tent, while her sister Eva wore a printed muumuu; Joanne Woodward was conservatively dressed in a white satin blouse and blazer and black pants; Stefanie Powers, ever the chic lady, arrived in a gray pinstriped trouser outfit; and as the hostess, I wore a colorful Pucci mini dress with matching tights and shoes, which caused Dick Crenna to joke, "Neile, it's a shame about your legs. I really do think that you should have had those varicose veins removed before you gave this party!" As for the men (Steve included), most of them wore turtlenecks, as befitted the times.

It seemed as if all of Hollywood was attending this party. At some point I heard Lee Marvin remark, surveying the crowd, "If the bomb hit tonight, the motion picture industry would be wiped out."

Because of the long driveway, we hired a tram for the evening to take our guests up and down the mountain. Terry and Chad had a wonderful time riding it up and down the road. Their main objective was waiting for the arrival of their idol, Adam West, then TV's Batman. Finally, at ten o'clock I had to put them to bed. When Adam at last arrived a half hour later, I took him by the hand and introduced him to the children. He was so sweet to them. When Adam retucked them in for the night they were the happiest kids I ever did see.

The very next day we were on our way to New York. Bob Wise was still editing the film down to the last hours before the first "official" screening. Still, we could feel the importance of this movie in Steve's career.

The rain and cold failed to dampen the crowd's spirits for the opening of The Sand Pebbles the night of December 20, 1966. The crowd started gathering outside the Rivoli at about seven o'clock, and by eight, the theater was jammed. There were Chinese ceremonial dragons bedecking the lobby and musicians playing. There were ladies in long dresses and furs and men in tuxedos. Penni Crenna looked sensational in a white ermine coat and I, still in my

Jackie Kennedy period, wore a long fur-trimmed magenta satin dress and coat. I remember spotting in the crowd Harry and Julie Belafonte and Pearl Buck and Hermione Gingold.

The rain and cold failed to dampen the crowd's spirits for the opening of The Sand Pebbles the night of December 20, 1966. The crowd started gathering outside the Rivoli at about seven o'clock, and by eight, the theater was jammed. There were Chinese ceremonial dragons bedecking the lobby and musicians playing. There were ladies in long dresses and furs and men in tuxedos. Penni Crenna looked sensational in a white ermine coat and I, still in my

Jackie Kennedy period, wore a long fur-trimmed magenta satin dress and coat. I remember spotting in the crowd Harry and Julie Belafonte and Pearl Buck and Hermione Gingold.

Directly after the screening, as Steve and I walked up the aisle, I looked at him and, barely able to contain myself, whispered, "What we have here, honey, is a real, honest-to-goodness, unadulterated, big-time moom pitcher star!" He laughed, pulled me to him, and agreed. "This is it, baby. We Have Made It. I know it in mah bones." Then softly he yelled, "Oooowee!!!"

From the theater we went on to the New York Hilton for a dinner dance that was benefiting the Pearl Buck Foundation and the Korea Society. After dinner we excused ourselves and joined some new friends at the Moroccan consulate. The Moroccan ambassador had already extended us an invitation to visit his country ("Not bad for a farm boy," Steve had said). We had met the Princess Laila Nezha and her lady-in-waiting, Kenza Alaoui, in Hollywood through Loretta Young and had liked them enormously. The after-hours party ended abruptly for me, however. I felt the flu bug hit me with a sudden vengeance. I fainted in the ladies room of the consulate and when Steve led me out I could envision the other guests whispering among themselves, "How awful about Mrs. McQueen getting crocked and passing out. Tsk, tsk. Just imagine!"

While we were in the city promoting the film, the studio put a big black limousine and a little gray Volkswagen at our disposal. Steve didn't like to be driven around - in a limousine or otherwise - unless it was absolutely necessary. The Volkswagen gave us the freedom to move about New York undetected and the limo provided the necessary means of escape when that freedom was threatened. The two cars traveled in tandem during the day while we promoted the new film and went shopping. Over the years Steve had adopted a way of walking down the street like he was in a mad hurry in order to prevent people from recognizing him until it was too late. Sometimes it didn't work and he'd have to make a dash for the limo. Still, he was grateful to his fans and never minded signing autographs (the only time he wouldn't was when the children were with him). His feeling was "It's all right, I always wanted to be someone, you know? And now that I am, all I've blown is my obscurity, and that's not much to blow." Because the crowds were sometimes huge and exhausting, he had had a rubber stamp made of his signature in Taiwan, and he would sometimes carry a stack of pictures with him which he would then pass out to his fans.

During this New York visit we ran into Richard Chamberlain. His musical Breakfast at Tiffany's had recently closed after its first preview. Steve asked Dick when he was coming back to California. "I don't know," said Dick. "New York's kinda nice. You have a big flop here and everybody still invites you to lunch and dinner. In California you have a flop and they cross you off the list." Dick Chamberlain's remark touched a nerve in Steve and troubled him momentarily. Like all actors, I suppose, he lived in fear that he would wake up one morning, and whatever it was that accounted for his talent would be gone. Fortunately, those first weeks of 1967 were wonderful. The critics loved his performance in The Sand Pebbles. The film had been rushed into a December release in order to qualify Steve and the movie for the Academy Awards. The studio's action had been justified. Steve's performance showed his enormous emotional range ("with all the simplicity and tenderness an actor can muster when he trusts his own virility," one reviewer said). Indeed, The Sand Pebbles is one of my favorite Steve films, although even then I found it excruciating to watch him in a death scene. For sheer entertainment, The Thomas Crown Affair is my favorite of his films.

By February Steve was riding high. He and Julie Andrews had just been voted World Film Favorites by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (the next day he woke Elmer Valentine out of a sound sleep with "Hello, Elmer. You are speaking to the world's most favorite actor!"), and he was nominated for an Academy Award for his role in The Sand Pebbles. (It was to be his first and only nomination.) We were in Palm Springs when we were notified. Steve was pouring concrete for the garage when I handed him the telephone. It was an exciting moment. He felt honored and overwhelmed. We roared down to Sambo's on his motorcycle, and we celebrated by ordering giant hamburgers and extra thick chocolate milk-shakes with vanilla ice cream. And then on March 21, 1967, three days before his thirty-seventh birthday, Steve McQueen became the one-hundred-fifty-third star to put his handprints and footprints on the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theater. Over two thousand fans were there and God knows how many photographers. In true Hollywood fashion, we arrived in Steve's burgundy Ferrari as the crowd cheered. Amid the pandemonium we learned that Steve had set an attendance record, equaling that of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell, who had together immortalized their footprints in cement.

By February Steve was riding high. He and Julie Andrews had just been voted World Film Favorites by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (the next day he woke Elmer Valentine out of a sound sleep with "Hello, Elmer. You are speaking to the world's most favorite actor!"), and he was nominated for an Academy Award for his role in The Sand Pebbles. (It was to be his first and only nomination.) We were in Palm Springs when we were notified. Steve was pouring concrete for the garage when I handed him the telephone. It was an exciting moment. He felt honored and overwhelmed. We roared down to Sambo's on his motorcycle, and we celebrated by ordering giant hamburgers and extra thick chocolate milk-shakes with vanilla ice cream. And then on March 21, 1967, three days before his thirty-seventh birthday, Steve McQueen became the one-hundred-fifty-third star to put his handprints and footprints on the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theater. Over two thousand fans were there and God knows how many photographers. In true Hollywood fashion, we arrived in Steve's burgundy Ferrari as the crowd cheered. Amid the pandemonium we learned that Steve had set an attendance record, equaling that of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell, who had together immortalized their footprints in cement.

Steve desperately hoped to bring home the Academy Award. He felt that if the Academy "went American" that year, he just might, "But if the voting goes English, then one of those cats will take the Oscar, probably Paul Scofield."

He was right. Paul Scofield won for A Man for All Seasons. But Steve was a good loser. Although once we were inside the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium he kept holding my hand and telling his stomach to settle down, he was riding high from the greeting the fans had given him when we arrived. It seemed they had reserved their biggest ovation for him, and he was feeling loved by the whole world. To him, being a movie star was better than being president ("Listen, in Taiwan most people don't know who Lyndon Johnson is, but they sure as hell know who John Wayne is"). As we were walking into the award ceremonies, a reporter asked Steve what he attributed his success to. Without hesitating, he looked at me and said, "Right there." It was one of life's magical moments for us.

Excerpt source: My Husband, My Friend, Neile McQueen Toffel, A Signet Book, 1986

Return to the Sand Pebbles Index