U.S. Navy (Retired)

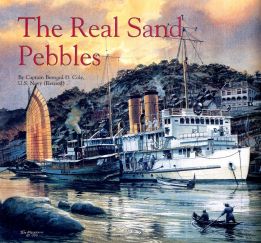

The construction story of the gunboats made famous by Richard McKenna's novel - soon to be re-released by the Naval Institute Press - and the classic motion picture starring Steve McQueen is one chock-full of problerns that involved design, shipping, and quality control - not to mention the Chinese Revolution.

estern

memory tends to be short-lived and highly selective, and Western

society rarely recalls that troops from several Occidental nations and

Japan once occupied China's cities, while U.S. warships, patrolled

China's rivers. We may have forgotten these events, but the Chinese

have not; the national collective memory of the "century of shame" is

never far from the surface in that country's dealings with foreign

nations.

estern

memory tends to be short-lived and highly selective, and Western

society rarely recalls that troops from several Occidental nations and

Japan once occupied China's cities, while U.S. warships, patrolled

China's rivers. We may have forgotten these events, but the Chinese

have not; the national collective memory of the "century of shame" is

never far from the surface in that country's dealings with foreign

nations.The U.S. naval presence in China dates from the earliest days of the republic: the 'Empress of China' arrived in Canton in 1784, the first ship flying the new U.S. flag to enter the China trade. Extensive interests in China have continued to form the heart of U.S. Pacific policy to this day.

The United States was not a participant in the mid-19th century wars against China, but it was quick to take advantage of China's undoing. Indeed, during the Second Opium War, in 1858, U.S. Commodore Josiah Tattnall justified open support of his British counterpart with the statement that "blood is thicker than water," ignoring the fact that the United States was not at war with China. And U.S. warships continued to follow their Royal Navy cousins on China's waterways.

The USS Susquehanna was the first U.S. warship to steam up the mighty Yangtze River, in 1853; a motley collection of ships followed over the years, typically those fit for no other duty. One was the USS Palos, the first gunboat to bear this name. Her arrival on the Yangtze in 1871 drew the scornful opinion of her fleet commander; Rear Admiral T. A. Jenkins, that:

"she burns a great quantity of coal, is slow, and draws too much water to go to many places that a gunboat of her tonnage should be able to reach; neither her appearance nor her battery is calculated to produce respect for her."

Until six river gunboats were designed and built in Shanghai in 1926, U.S. naval and diplomatic officers, businessmen, and missionaries in China made such remarks frequently.

Early in the 20th century, U.S. interests in China continued to increase, as businessmen and missionaries expanded their solicitation efforts. This accelerated activity in a China torn by revolt and unrest led to demands for increased naval presence, which was formalized in the creation of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet (and the Yangtze River Patrol) in December 1922. Service on the Yangtze, a river of 1,500 navigable miles marked by frequently shifting channels, sharp bends, and currents of more than 14 knots, demanded ships with maneuverability, speed, and sturdiness. An upper Yangtze River inspector sounded the common theme in 1924; "Vessels should be of adequate dimensions, speed, and have powerful haulage equipment" to combat the river's natural and manmade hazards.

The first "modern" U.S. warships arrived on the Yangtze only in 1903, when the USS Villalobos and USS Elcano arrived from the Philippines, where they had been captured from the Spanish in 1898. The ships were hot, dirty, and poorly ventilated. They also were underpowered, underarmed, and generally unsuitable for river duty; but they patrolled the Yangtze for a quarter-century nonetheless.

By the turn of the century the China station was perhaps the most sought-after assignment in the USS Navy. Americans were above the law there, and most hedonistic pleasures were readily and cheaply available.

The Navy succeeded in funding two new river gunboats in June 1912. The USS Monocacy and USS Palos were built to plans from Yarrow Company, a Scottish firm that had built gunboats for the Royal Navy. They were constructed at the Mare Island (California) Navy Yard, then broken down for shipment to China, where they were reassembled.

While describing the need for new river gunboats for China was easy enough, detailing their characteristics and gathering design information to get them funded was quite another matter. The Monocacy and Palos remained distinctive. The General Board noted in November 1917 that "gunboat no. 22" had been authorized by Congress but not appropriated for and requested that river gunboats be requested again in 1918. These craft were included in the General Board's shipbuilding programs for 1920 through 1924, but to no avail.

The Asiatic Fleet commander at the time, Admiral W. L. Rodgers, was of course a strong advocate of new gunboats. He also extolled the virtues of Shanghai's Kiangnan shipyard as a likely contractor for new gunboats, noting that the yard had British managers and previously had built freighters for the U.S. Army.

In a 21 February 1923 message, Rodgers said that a gunboat "speed 16 knots length 200 feet draft 5 feet can be built including all machinery except ordnance at Shanghai. Delivery 12 months cost $400,000." The admiral recommended "four replacements this year." The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Robert E. Coontz, also received a picture of a "TwinScrew Passenger & Cargo Steamer Specially Desined and Built for the Upper Yangtze Service Between Ichang & Chungking" by Kiangnan Dock and Engineering works of Shanghai, a supporting