...I arrived in Taiwan, as scheduled, in late November,

excited and ready for more.

Taiwan was what they call a "rough location." In 1965,

Taipei was far from the Eden of the Orient, the garden spot

of the Far East. The city was famous for its spectacular

National Museum and its exotic brothels (not necessarily in that

order-especially for the troops sent there from Vietnam for

a week of R and R). It had no discernible traffic pattern: the

thousands of taxis and pedicabs bounced off each other

routinely like fun-fair bumper cars; and municipal plumbing

had not yet been introduced, so that one stepped gingerly

over the gutters of human waste that crisscrossed a city that

simmered in sewage and reeked of latrines.

After our arrival, cast and crew were assembled for

Thanksgiving turkey in the Army PX and given a pep talk to

prepare us for the long months ahead. We were granted

limited passes to the Army base, where, on occasion, old

John Wayne movies were shown for the military; but we

were advised, for our own safety, to stay in our hotels at

night. By day as well, the actors were restricted to hotel

grounds and put on official "standby" because of an intricate

shooting schedule that, depending on weather, river tides

and currents, was hourly subject to change.

If I had my foolish heart set on exploring during this film,

using Taiwan as my travel base in the Far East, it served me

right to be brought up short. Not only weren't we allowed to

leave the island, but we weren't allowed to leave the hotel.

My detailed dreams of weekends in Hong Kong, side trips to

Saigon, Angkor Wat, Manila-all dashed to smithereens.

My attitude on the film was less than professional, resenting

as I did the constraints imposed on the cast-notably me.

I was unfamiliar with such production procedures: the only

location I'd ever been on was the lower East Side - not the

Far East. After waiting for hours without working on the

Shanghai dock set, I would wander off at will with my

cameras, certain I would never be called, to photograph funeral

processions, puppet shows, temple rituals, leper colonies -

anything I found of interest in the small rural villages

nearby.

In the role of Shirley Eckert, missionary-teacher, I was

the essence of earnest, the soul of selflessness staring

wistfully into the waters of the Yangtze in my summer seersucker

and floppy straw hat. An angel of mercy come to save my

fellow man. Far from type-casting for one who hadn't lifted

a finger to save her fellow pheasant-for a girl hot from a

fall shoot. And during the filming, little of Shirley's

selflessness rubbed off on me.

One day I disappeared from the set to photograph a

Taoist religious ceremony in the middle of a rice paddy

where young barefoot initiates walked, entranced, through a

bed of white-hot coals, unblinking and unscathed. When I

was needed for a large master shot and couldn't be found on

the set, they made it without me, only to have to set it up

again and reshoot it when I reappeared, moments later,

nonplused. No sooner would I return than Steve McQueen

would take off on his motorcycle, while the insurance

representative blanched, or jump onto the back of a passing water

buffalo and get bucked off in the mud. And the crew would

settle down to wait again.

Steve was friendly during the shooting, inviting me to dinner

in the house rented for him with his wife, Neile, and

kids; advising me-in a well-meant attempt to get me to

"loosen up"-that what I really needed was to "get it on"

with some of his buddies.

His buddies were hardly my idea of heaven: he'd arrived

in Taiwan with a commando unit of six stunt men, none

under six feet and all ex-Marines. They were like his

personal honor guard, and when he moved, they jumped. Hard-

drinking, hard-fighting - as time on the island ticked by,

McQueen and his gang grew increasingly restless and often

spent nights on the prowl, roaming the little city, drinking,

heckling, picking fights and pummeling.

Coiled, combustible, Steve was like a caged animal. Daring,

reckless, charming, compelling; it was difficult to relax

around him-and probably unwise-for, like a big wildcat,

he was handsome and hypnotic, powerful and unpredictable,

and could turn on you in a flash.

He seemed to trust no one and tried constantly to test the

loyalty of those around him, to trap them in betrayal. Yet for

one so often menacing, he had a surprising, even stunning,

sweetness, a winning vulnerability.

He seemed to trust no one and tried constantly to test the

loyalty of those around him, to trap them in betrayal. Yet for

one so often menacing, he had a surprising, even stunning,

sweetness, a winning vulnerability.

But he seemed to live by the laws of the jungle and to have

contempt for those laid down by man. He reminded one of

the great outlaws, a romantic renegade; an outcast uneasy in

his skin who finds himself with sudden fame and fortune.

One had the sense that it came too late and mattered little in

the end. And that he tried to find truth and comfort in a

world where he knew he didn't belong.

On one of those rare days when the cast and crew were all

accounted for, the weather well-behaved, the tide up and the

current steady, Wise had just called "Action" on the prow of

the gunboat when in the distance what looked like a herd of

seals appeared, shiny black heads bobbing, swimming slowly

but surely into the background of the shot. A launch was

dispatched to investigate and returned with the information

that they were not, in fact, seals but Nationalist frogmen

training to recapture the Chinese mainland, and so we

waited forty-five minutes until they swam past and out of

frame.

It was oddball incidents such as these, coupled with unruly

tides and uncooperative weather, that helped lengthen our

stay in Taiwan from two months to four.

Of that time I worked, at most, three weeks. Over the

other thirteen I paced my Golden Dragon Suite in the Grand

Hotel (once occupied by Ike and Mamie Eisenhower), read

so much I thought my eyes would fall out, and ordered room

service. Food assumed mythical proportions, and, by the

time I left, so did I.

While eager for "exotic locations," I was innocent of their

downside disadvantages. "Exotic" locations were, by definition,

difficult: out of touch, hard to reach. Alien. Strange.

What's "colorful" for the tourist becomes uncomfortable for

the new resident, who, a few weeks after arriving, slides

stonily into culture shock from so much color. So many rice

paddies. So much night soil. So little plumbing. So much.

"Mongolian barbecue." So many water-buffalo burgers. So

much Mandarin. So little English. And months of reading

Stars and Stripes.

If my first film was all women, my second was all men: the

actors played sailors by day and sailors by night-banding

together, tearing up the port, drinking, carousing, "cruising

for a piece of ass." I hardly regretted not having that option,

but I was lonely nonetheless.

The spar I clung to in a sea of strangers was Richard

Attenborough, then one of Britain's leading character actors

- a terrifically bright and enthusiastic man who energized a

room upon entering it. He was a veteran of long locations

and knew how to cope and what to expect. He filled his free

time acquiring art and informing himself on the island's

poliitics, making underground contacts with the clandestine

opposition on Taiwan.

With him, I felt instantly at ease. Over long Chinese dinners

we discussed our interests. He told me that his dream

was to direct a film on the life of Gandhi and asked if I would

play the cameo role of Margaret Bourke-White, who had

photographed Gandhi shortly before his death; he thought

I resembled her. I smiled and told him she was one of my

heroes; I was flattered to be asked.

He hoped to begin the project as soon as possible, he said,

and was funneling all the proceeds of his acting into its

development. But in spite of his passionate conviction, for the

moment Hollywood wasn't buying it: the life of a little brown

man spent in fasting and spinning-who would pay to see

such a film?

I made other friends on Taiwan: American bureau chiefs

who briefed me on the island and generously took me on

tours; U.S. military brass and eccentric Europeans living in

self-imposed exile; and Taipei's diplomatic circuit, whose

dinner parties I attended. But these were strangely doomed

and depressing dinners, for Taiwan, at that time, was the

kiss of death for a diplomat and his family-the last living

post for officers of protocol, the place diplomats were sent to

die. Languishing in their Taiwanese teak, comforted by

crates of consular Scotch, they recalled once promising futures,

brooded on their failures and ignored the steady

glares of resentful wives.

I missed my home. My parents and my brother-my

brother, growing bigger by the day. I missed my friends. I

missed America. I even missed California: I dreamed of

Disneyland and the House of Pancakes. Hamburger Hamlet.

Thirty-one Flavors. I had had enough adventure. Enough

exotic. I wanted to go home.

Finally, after four months, we moved on for another

month's shooting in Hong Kong-the Big Apple of the Orient,

Gateway to the East. Now this was more like it, more

what I had in mind: Hong Kong was humming, and there I

was happy; free, at last, to leave my room, discover, explore,

make friends. Journalists and old hard-core colonialists led

me through the mysterious maze of the walled city, took me

sailing on sampans, on rickshaw rides around Macao, and

down into dank opium dens. By the time we'd finished in

Hong Kong, I'd settled in and made a fine life there; I was

in love with the city and hated to leave.

We assembled again in Los Angeles for the sixth and final

month of shooting at the Chinese mission reconstructed on

the Fox Ranch in Malibu; I returned to a bigger, blonder

brother and the comforts and coziness of home, where I

celebrated my twentieth birthday. Yet no sooner had I finished

the film than I was off again on another trip, a travel

opportunity I couldn't resist.

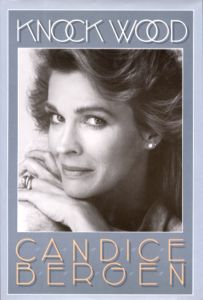

Excerpt source: Knock Wood, Candice Bergen, Linden Press/Simon

Schuster, 1984

|